In a media-possessed world where perception is reality and calling 458-666-HELL returns the voice of Nicolas Cage in full-tilt serial killer sicko mode, it’s no wonder that Osgood Perkins’ nightmare-fueled procedural is set to clear $20 million in its opening weekend, more than doubling boutique distributor NEON’s previous total box office best. In manufacturing a viral campaign around the cursed images and atmosphere set forth by the son of horror’s most recognizable cinematic icon Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), NEON proves that when you imbue months-long devilish dread with a dash of Nicolas Cage at his most feral you might just turn a lot of ass-clenched civvies into pureblood horrorphiles.

Capitalistic enterprises aside, Longlegs ultimately settles into a fairly conventional crime procedural. Heightened by an off-kilter brand of wide-angle photography that stretches reality and an editing style that pulses as if aligning to the BPM of Satan himself, the mundane and cold suburbia where Longlegs conducts his crimes quickly becomes the scenery of an immersive landscape where hell creeps into our backyard. While the technical wizardry of Oz is on full display as the bare-bones nature of the plot unfolds, the question becomes: how far are we willing to allow tone and atmosphere to carry the minimal plot forward?

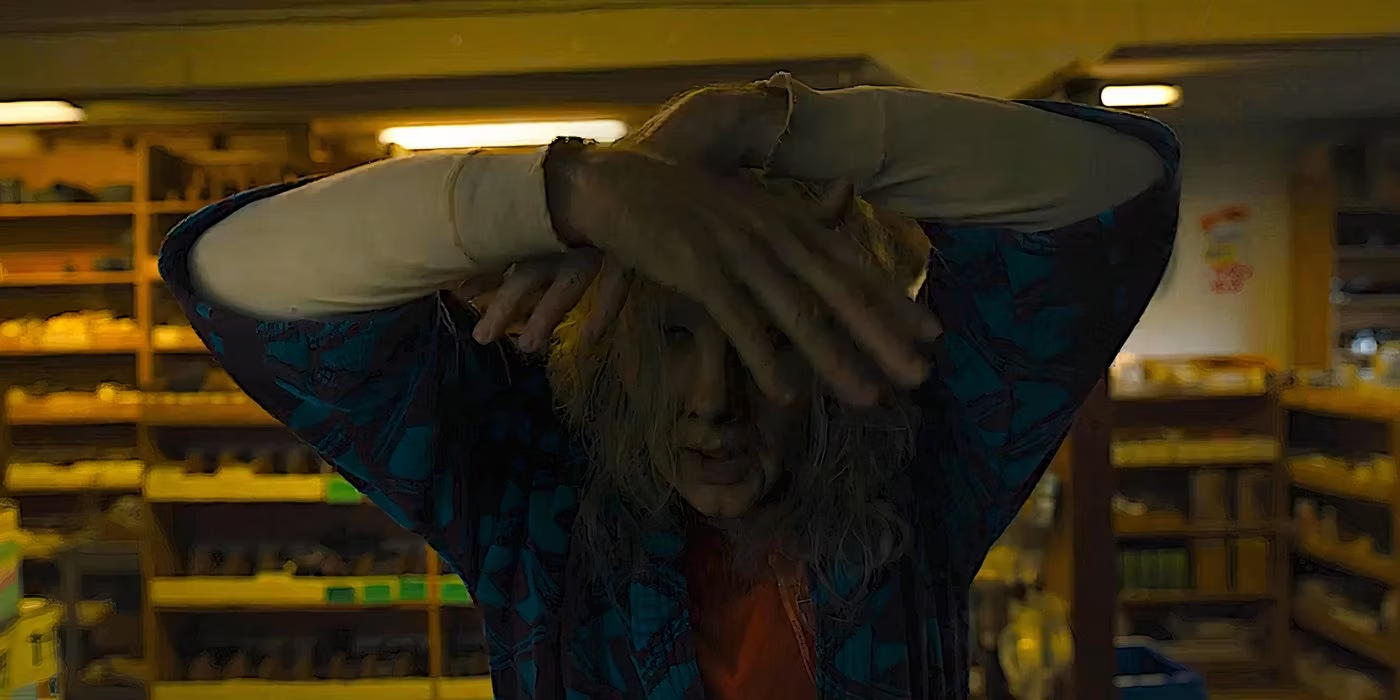

Matched in that nervous tone and delivery with a certain glazed-over uneasiness about the world is our protagonist Lee Harker, played by the certified scream queen of It Follows, Maika Monroe. Asked early in the film, “Is it scary being a lady FBI agent?” she channels the legacy of Clarice Starling and responds in her trance-like emotional detachment, “Yes, yes it is.” This straightforward yet eerily foreboding sentiment only begins to invite the horrors she is yet to encounter.

Bouts of psychic-coded investigations and too-close-to-home confrontations signal that something deeper is afoot between Harker and Longlegs. Something supernatural may be manipulating the safety and security of our minds. Or–and potentially even more sinister–someone is making us believe in that paranormal proposition. Whatever the case may be, bodies begin to pile and Harker is at the epicenter of a case marked by a series of unexplainable murder-suicides taking place over 30+ years.

With this setup, the box set of pre-packaged perceptions contains no less than a multitude of referential items: a crime drama as sick as the hunt for John Doe, a serial killer so psychologically demented you have to pay for a ticket to witness his face, and an agent thrust into all nine circles of hell welcomed by only the likes of Buffalo Bill or the Zodiac killer. In parts, Longlegs exhibits indications of all these precursors. A trail of ciphered but signed letters, the implausible invisibility of physical evidence, and a documented pattern of brutally annihilated families characterize the path by which the titular sociopath lays waste. While these well-documented fixtures of David Fincher and Jonathan Demme conjure a familiar path forward, after nearly an hour it’s even more evident that Perkins is not interested in the process of the investigation beyond its role as an entry point for more significant plot interests.

This brings the influence of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997) much closer to the foreground. With a first-class second-act that suggests a multitude of paths forward from the climax of a well-earned and Polaroid-spurned jump scare, the amount of viable and fascinating narrative directions seems impossibly infinite. Unfortunately, it also seems possible that the script chose one of the least provocative routes from this point forward. Perkins held pocket aces at the turn, yet he folded to the bluff of an underwhelming close.

Opting to allow the film’s most valuable asset of terror to (literally) faceplant out of the picture first betrays the marketing that entertains audiences by refusing to reveal Cage. In doing so, it offers a trade: buy a ticket and be rewarded with the visual manifestation of the film’s greatest evil (presumably for the entire runtime). Second, and more damning on the part of Perkins, is that redirecting the narrative away from Longlegs also makes the statement that Perkins believes the redirected alternative to Cage is just as interesting to follow. In short, it’s not.

In long, Longlegs as a character has an unexplored richness. He almost undoubtedly fried one too many brain cells on the devil’s lettuce (and many more of his garden of delights) while following the Kiss concerts of the 70s, yet the film does not invest enough time in him as a character to sufficiently understand what makes him tick. A greater sense of motive beyond this speculative inference would have catapulted him into the Rushmore of cinematic serial killers. Even the formidable effort of the narrative alternative after Longlegs’ departure (Ruth Harker played by Alicia Witt), and the deep-rooted mommy issues her storyline presents cannot compare to the unhinged space where Cage stands alone. That space is left untapped for its maximum potential.

Before the collision of sheer physical will and the solid wood of an interrogation table, Perkins offers a hint of self-awareness regarding Longlegs’ tonal shifts as a character. At one extreme, he is incoherently cuckoo for the algorithmic birthdays of young girls. But in a far stronger and scarier moment of characterization, he is operating in the grounded seriousness of a sick, dissociated, and obsessive individual either cast aside by society or self-isolated by an undefinable variable. Trending in the direction of carrying that intensity into the conclusion, the aforementioned self-awareness evaporates, giving way to a filmmaker still lacking the confidence to embrace the ambiguity of his nightmare premise.

When you make the centerpiece of your story a character so disassociated by their delusions that they are willing to kamikaze into a table for their cause (“Hail Satan,” am I right?), one would reasonably expect the remaining stretch of the film to be more richly informed by his direct or indirect presence. What we receive, however, is an abandoning of the highly textured psychological disorientation of the first two acts highlighted by the interrogation and a harsh pivot into a more tangible threat. We are left with the speculation that the dark enchantment of Longlegs will live in the post-traumatic suffering of the agent responsible for his capture, but even she is left tenuously explored as a mere slave to the circumstances around her.

Suppose for a moment that on the surface it comes as a surprise that the director of Gretel & Hansel (2020) would be the mind behind what has been promised to be one of the scariest theater experiences of the 21st century. Most likely you, me, and most others who fell victim to mildly misconstrued, albeit atmospherically inventive marketing, must look no further than the director’s most recent feature to encounter the fundamental core of this multi-tonal endeavor: the fairytale. Despite its third act shortcomings, what is present is the hero overcoming evil, the ambiguity of a past historical setting, and the presence of magic and mythological objects. The beats of a realm in which Perkins has treaded are invariably present. The essential question to the fairytale theory then becomes: what is the moral of this story? Does this outcome bring us to the land of happily ever after?

This is the decisive touchpoint in which Osgood Perkins–the writer, and Osgood Perkins–the director exhibit symptoms of early onset multiple personality disorder. Two-thirds of the film recognizes the horror genre’s greatest strength: the fear of the unknown and the helplessness of battling a demon we cannot see. Its finale diverts into well-worn iconographic and thematic territory burnt out by an exposition dump that breaks the Richter scale of unrealized potential. The feeling that a moral lesson was within reach on the greater musings of evil found within the ordinary is inevitable for a conclusion that volunteers away its beguiling set-up in favor of allowing unexplainable realities to be explained with unsatisfying exactitude.

There is undeniable skill exerted in the direction of the performances, the craft of the visual imagery, and the realization of an atmosphere that can make even the most desensitized of horror fanatics feel a faint sense of illness. However, when merging that dastardly environment with the highest volume import of plot delivered in the rushed manner of a filmmaker lacking the closing precision of the cinematic greats, the film’s long legs are desperately stretched out a bit too far. For all the preexisting generic frameworks this film will be characterized by–the police procedural, the paranormal possession, the psychological serial killer–its most inventive format lurks deep beneath the surface. Osgood Perkins’ greatest fairytale does not feature witches in the woods. Rather, it is shrouded by the darkness of the devil hiding in our heads.

Review Courtesy of Danny Jarabek

Feature Image Credit to NEON via Entertainment Weekly

Recent Comments